Milestones in Publishing the Spanish and Portuguese Prayer Book in London

in Blog

By Dr Roy Shasha, Jerusalem

Introduction

The year 2017 marks the publication of the first new British edition of the Spanish and Portuguese prayer book in over 100 years. This achievement represents the culmination of many years of planning, a major re-editing of the text and the preparation of a new translation by a small body of dedicated professional staff and a larger number of equally dedicated volunteers. Therefore this is perhaps an appropriate moment for us to stand back and view this achievement within its historical context.

An excellent brief history of the printing of the Spanish and Portuguese prayer book was written by Hakham Gaster in the introduction to his edition of the prayer book, and the writer wishes to acknowledge his debt to this important piece of work. However, the intention and scope of this work is very different to that of Dr Gaster in a number of respects.

- We have attempted to list all Spanish and Portuguese prayer books planned, printed or edited in London, including a number that were not authorised by the Mahamad and one that was written but not published. Also included are all the known Spanish translations of the text prepared in London.

- Each volume seen has been described in a precise bibliographical fashion, and as far as possible not only reprints, but also bibliographical variants have been noted.

- Each edition has been placed wherever possible in a historical context. A brief biography of each editor or translator has been included, together with information as to how the books were distributed.

- Many important noteworthy or unusual features of the editions have been elaborated on. Also the addition of any new features, such as the prayer for the bar mitzvah boy and the naming ceremony for a girl, has been described.

- This history also includes developments that have taken place since the Gaster history was written

The development of publishing the prayer book in England according to the Spanish and Portuguese rite is a complex and perhaps to a modern audience, a somewhat strange story. The major participants in our story include two generations of gentile printers and publishers, E. Justins and W. Justins; two Ashkenazi entrepreneurs, Alexander Alexander and the Abrahams family; and two very remarkable Ashkenazi scholars, David Levi and Rabbi Dr. Moses Gaster. The Sephardim themselves were remarkably inactive in this arena for considerable periods in our story. Hakham Isaac Nieto produced a Spanish- only set of prayer books as well as a partial edition of some of the high festival prayers in Spanish and Hebrew. Only one Sephardi scholar and employee of the congregation, Reverend David De Sola, who was not even English born but an import from the mother congregation in Amsterdam played a prominent role in producing a Hebrew-English prayer book, until the 21st century.

Almost absent from the saga (until the turn of the twentieth century) is formal Congregational sponsorship and participation in the process of publishing and distributing the prayer book. Indeed some of the sales outlets used would appear to us highly unconventional, although normal for that time. A. Alexander advertised on the title page of the first edition of his daily prayer book in 1773 that it could be purchased at ‘Sam’s coffee shop near the Great Synagogue near Aldgate’. This institution was in Duke’s Place, which today is in between St. Mary Axe (the current site of the Gherkin) and Aldgate Underground Station. It was run continuously by the Joseph family for about 100 years, closing only in the 1890s. This shop also sold the second edition of David Levi’s edition of the prayer book. In 1789 David Levi had the first edition of his prayer books distributed by two firms of general publishers and book-sellers: Joseph Johnson of St Paul’s Church-Yard and Parsons and Walker of Paternoster Row. This is a far cry from today’s centralised synagogue official ordering system based in Ashworth Road.

In the background of any attempt by Yehidim to print religious material lay the exceedingly strong hand of the Mahamad, whose permission congregants required for its publication. The gentlemen of the Mahamad possessed extraordinary powers of censorship, and used them for reasons that are not always clear, as we shall discover. Another remarkable feature of the story is the strong attachment to the use of Spanish as opposed to English as a language into which to translate the prayers. It was not until almost 120 years after the Resettlement of the Jews in England (and almost 300 years after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain) that a prayer book both in Hebrew and English was finally printed, and 200 years after the Resettlement that the Heshaim officially took responsibility on behalf of the congregation for printing and distributing the prayer books.

Remarkably, just as the Sephardi Congregation was indebted to three Ashkenazim, A. Alexander, David Levi and Rabbi Moses Gaster, so too are the Ashkenazim of England indebted to the Sephardim for some of their most popular translations. Rev David De Sola worked on a translation of the Ashkenazi festival prayer book (London, 1st edition 1860, 9th edition 1945). This translation was started by Reverend De Sola and completed after his death by his son-in-law, Reverend Abraham Pereira Mendes, who also translated the Ashkenazi daily prayer book into English (London 1st edition 1864, 4th edition 1904).

Let us examine some features mentioned above in order to help us understand some of the facets of the books that we will describe.

- Censorship

Perhaps the strangest aspect of our tale to the modern reader is the strict censorship imposed by the Mahamad on religious materials printed by the members of the congregation. Rigid self-censorship was not unique to the London Sephardi community, as it was introduced in the Ferrara Sephardi community in 1554, followed by the Sephardi community of Amsterdam in 1639 and the London community had this power probably since its inception in 1656. However, in England there was a unique additional reason for adopting self-censorship. John Thurloe, the Secretary to the Council of State in Protectorate England, specified in the 1656 minute of the Council that one of the conditions of the Resettlement was ‘that they [the Jews] shall not be allowed to print anything, which in the least oppose the Christian Religion, in our language’, and the responsibility for ensuring this was taken most seriously by the Mahamad.[1] However, the Mahamad apparently also used its powers of censorship to control the printing of secular literature too. In 1734 Jacob de Castro Saramento requested and received permission to produce an English-Portuguese dictionary.

What is relevant to our story is the fact that the Mahamad used its powers in order to control the printing of prayer book for reasons that are not known to us, and there is evidence of this on three separate occasions.

In 1721 one of the rabbis of the Heshaim, one Joseph Messias, published a Spanish translation of the prayer book without the consent of the Mahamad. Only one copy is known to survive and the strange story of its discovery and a description of the item may be found in the Miscellanies of the Jewish Historical Society, part 4, pps. 95-101. Its’ finder, and the author of the article, Reverend. M. Rosenbaum, suggests that Messias may have had differences with the Mahamad and printed the book without their approval. In order to avoid punishment he may have voluntarily recalled or bought back all copies in circulation, and the matter was taken no further by the Mahamad. This book is now in the Leopold Muller Memorial Library, Oxford.

Some ten years later the power of the Mahamad was sufficient to block yet another attempt to print a prayer book with an English translation. In 1734 Hakham Isaac Nieto’s brother, Moses Nieto, requested permission from the Mahamad to print a translation of the prayer book into English, but permission was refused.[2] The manuscript still survives and was auctioned in Christies New York on 24 June 1998, sale no. 8105, lot 395.

Courtesy of Kestenbaum and Co Auctioneers New York.

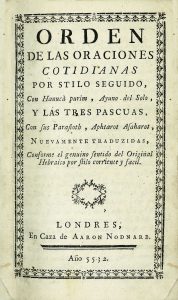

In 1772, a year after an authorised London printing of the daily prayers in Spanish by Hakham Isaac Nieto, a further Spanish translation of the daily and festival prayer book was published in London by one Aaron Nodnarb, which appears to have to have been the pen-name of Aaron Brandon, whose name appears in a list of Yehidim in 1764. Since this book was apparently printed without the authority of the Mahamad, it is probable that he attempted to bypass the official-permission process, possibly because he had issues with the Mahamad.

- Official Patronage and Participation of the Synagogue in the Publication of the prayer book.

In the early years after the Resettlement there was limited formal participation in the production and distribution of prayer books. The first prayers published in London specifically for the Sephardi community in the early 1700s were in Spanish only, and consisted of extracts of the High Holyday liturgy printed in Spanish for the benefit of those who had recently returned to Judaism.[3] They appear to have been issued by the Mahamad and to have been distributed to worshippers free of charge on the High Holydays.[4] All the subsequent publications of the prayer book until the Gaster edition of 1901-1906) were private initiatives. Neither the mother community in Amsterdam nor the Ashkenazi community in London had any connection with the publication or distribution of the prayer book for most of their history.

- Loyalty to the Spanish and Portuguese languages.

The community for many years employed Spanish and Portuguese rather than English as a vernacular in the synagogue. Sermons were for many years preached in Spanish by the Rabbis of the community, although they were sometimes published in English.[5] However, the first English sermon was not preached in Bevis Marks synagogue in English until 1831, almost 200 years after the Resettlement of the Jews in England and 350 years after the Expulsion from Spain. There are to this day remnants of this Portuguese in the synagogue service, since the allocation of Mitzvot is still done in a mixture of Hebrew and Portuguese.

The minutes of the London congregation were kept in Portuguese until 1819. The first congregational publication of bye-laws in English was the bye-laws of the Society מכסה אביונים (‘Clothing for the Needy’) in 1822.

4. The parochial nature of the publications.

Most if not all of the prayer books were printed for use in London, more specifically in Bevis Marks and branch synagogues of the congregation. There is no evidence that they were produced for the benefit of the American or Canadian markets, although some were used there. Hence, amongst the other unusual features of some of the editions of the Spanish and Portuguese Prayer book are inclusion of tables of times of services in Bevis Marks and tables of the times of Shabbat as well almanacs at the back. This feature can also be found in some Amsterdam prayer books as well.

Let us now examine some major mile-stones in the history of the publishing the Spanish and Portuguese prayer book. Because the publications were the uncoordinated work of private individuals, some of these initiatives overlapped, and there may have been some element of competition between the parties concerned. To keep our presentation clear, the prayer books are ordered by date of first print of each edition by each editor, rather in strict chronological sequence of publication.

The volume of material that could be included is considerable. Apart from orders of service for special events, there were congregationally published prayer books for lifecycle events, special prayer books for children and Haggadot. Here we can offer only a selection, and so have limited ourselves to every known Sephardi prayer book published in London that covers daily or festival prayers, issued within the community.

The editions we will examine are those of:

- Hakham Isaac Nieto

- Alexander Alexander.

- David Levi.

- Rev David De Sola.

- Dayan Abraham Haliwa.

- Ann Abrahams and Son.

- Hakham Moses Gaster.

- The 2011 Heshaim edition.

Before we commence our journey, it is appropriate to point out several things. Firstly, the congregation was founded mainly by families from Amsterdam. We have no evidence as to which prayer books were used in the synagogue from the time of the Resettlement till the publication of the first payer book in London over 100 years later, although we can assume that they would have been mainly from Amsterdam. Further, as we shall see, the Amsterdam minhag itself underwent certain minor changes during the period. Subtle differences also developed between the minhag of Amsterdam London and New York. Hence the term Spanish and Portuguese minhag is a term with some limited degree of flexibility. However, these minor differences and their evolution are beyond the scope of this history.[6]

I would like to thank all those who have assisted me of the preparation of this piece. In particular, I would like to thank the Thesoureiro of the Heshaim, Dr. Jeremy Schonfield for his kind assistance and advice, and also the valuable comments of the honorary archivist of the Congregation, Miriam Rodrigues-Pereira. I am also indebted to Dr. Aron Sterk who also made a number of helpful suggestions. However, many other people have also helped, advised, and encouraged in a variety of different ways. Without their all their help this project would be much poorer and I am grateful to them all.

Bibliography:

Gaster, M., The History of the Ancient Synagogue of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews in Bevis Marks. A Memorial Volume 1701-1901 (London: Harrison and Harrison 1901).

Hymanson, A., The Sephardim of England (London: Methuen & Co ltd 1951).

Roth, C., Magna Bibliotheca Anglo-Judaica 2nd edition (London: The Jewish Historical Society of England 1937).

Roth, C., ‘The Marrano Typography in England’, Library: Transactions of the Bibliographic Society, (1960) S5-XV (2) 118-128.

Sterk, A., “Rylands Gaster MS 1595: A late 17th or early 18th century English translation of the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish Prayerbook for the use of a woman” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library (forthcoming)

Sterk A., http://www.timesofisrael.com/mystery-surrounds-mistake-filled-ancient-prayer-book-found-in-uk/

- Hakham Isaac Nieto

Hakham Isaac Nieto (1687-1783) was the son of Rabbi David Nieto, Hakham of the London Congregation from 1701 to 1728. As was mentioned previously, the first liturgical publications of the synagogues were selections of prayers for the High Holydays. These are attributed to Isaac Nieto, even though his name does not appear on the title pages. Hakham Isaac Nieto served as Hakham 1732-40, and was Ab Beth Din 1751-6. His relationship with the Mahamad was not easy and he resigned over the appointment of Rabbi Moses Cohen d’Azvedo, the son-in-law of Hakham Moses Gomez de Mesquita, as a Dayan on his Beth Din without his consent. After his resignation, Hakham Isaac Nieto became a public notary, however he did retain some involvement with synagogue affairs. In addition to the Spanish translations of the prayers, a number of his sermons were also published.

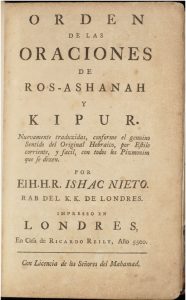

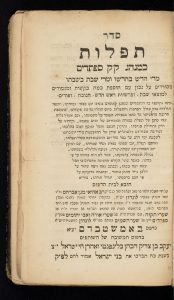

Prayer books

Orden de las Oraciones de Ros-Ashanah y Kippur. Prayers for Rosh Hashanah and Kippur in Spanish only. Translated by Hakham Isaac Nieto, together with a calendar written in Spanish and also prepared by Hakham Isaac Nieto covering 1740-1761. Printed by Richard Reily, London, 1740.

Published with the permission of the Mahamad.

Size: 12 cms x 18 cms.

Pagination: xvi, xxvii, 578, 24.

The prayer book commences with a lengthy introduction on the subject of prayer. There follows a translation of the poem Keter Malkhut by Solomon ibn Gabirol, which a rubric instructs one to recite on the morning of the Day of Atonement. This was also the tradition in Amsterdam, as witnessed by the rubric of the Rosh Hashanah and Kippur prayer book printed there in 1689 by Joseph Attias. In more recent years it was recited in the evening there, but is today no longer part of the formal service. No other London or early American Spanish and Portuguese prayer books indicate when it is meant to be recited, but the New York de Sola Pool edition (p. 67) states that it is recited in the evenings.

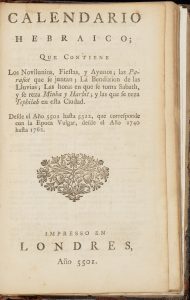

The calendar at the back of the prayer book marks the start of the tradition of printing the calendar in the London Spanish and Portuguese prayer book. Apart from listing dates of Jewish festivals, it includes a list of forty important dates in Jewish history, as well as times of services at Bevis Marks.

Hakham Isaac Nieto issued a second calendar in 1763 covering the next 24 years, and the Nieto family appears to have sustained an interest in the Jewish calendar. Hakham Isaac’s father David wrote a book entitled Pascalogia, printed in Cologne in 1701, comparing the Hebrew calendar with those of the Roman and Greek Churches, and discussing the discrepancies that had arisen between them. He also prepared an almanac for the years 1717-1740 entitled Binah La’itim, printed in both Hebrew and Spanish editions. Hakham Isaac’s son Phineas compiled an almanac for the years 1790-1840, and a descendent, Reverend Abraham Nieto, published an almanac for the period 1902-2002, which was printed in New York.

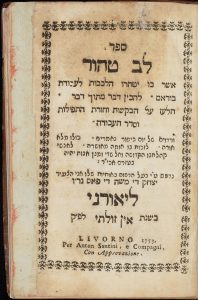

The Yom Kippur translation was reprinted in Livorno in 1763 under the name ספר לב טהור with the Hebrew and Spanish appearing in alternate paragraphs.

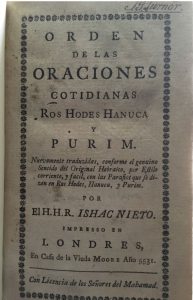

Orden de las Oraciones Cotidianas Ros-Hodes Hanuca [y] Purim. Prayers for weekday, Rosh Hodesh Hanukah and Purim in Spanish only. Translated by Hakham Isaac Nieto and printed by the widow of John Moore, 1771.

Published with the permission of the Mahamad.

Pagination: 1, vii, viii, vi, 277, 2.

Further reading:

Israel Solomons, ‘David Nieto and Some of his Contemporaries’, Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England, 12 (1915), Appendix 1, ‘Isaac Nieto and his Works’.

- Alexander Alexander and his son Levy

Alexander Alexander (1742-1801) was an Ashkenazi who worked for the printer Moses Hertz Hague from 1770 to 1773, and whose name is recorded as a typesetter for the second volume of הדרת מלך, a commentary on the Zohar by Rabbi Shalom Buzaglo. He was the first person to translate and publish the entire Spanish and Portuguese liturgy into English. He initially used the press of a gentile printer, J. and W. Richardson, before acquiring his own, the first Jewish press in London. Prior to translating the Sephardi liturgy Alexander produced an Ashkenazi prayer book translated into English in collaboration with B. Meyers. Both were printed in London in 1770 by W. Tooke. In the same year he also printed two Haggadot, one for Sephardim and one for Ashkenazim printed by W. Gilbert.

Alexander’s knowledge of the Sephardi pronunciation appears to be questionable. Each paragraph of the translation is prefaced with a transliteration of the first few words of the Hebrew in italics. However, he consistently appears to employ a Germanic pronunciation in this transliteration. On page 8 of the Daily and Occasional prayers for example the phrase רבונו של עולם is transliterated as Ribonow Shel Owlom.

Since the translator was not a member of the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation his publication did not require permission from the Mahamad. As mentioned, Moses Nieto, the brother of Hakham Isaac Nieto, had prepared an English translation some forty years earlier, for which the Mahamad refused permission. In 1766 an American, Isaac de Pinto, published a translation of the prayer book in New York, where Hymanson (p. 184) suggests it was printed because the Mahamad refused consent to do so in London. However, as he was a member of Sha’erith Israel Synagogue in New York he would have had no reason to print it in London.

Levy (Yehudah Leib) Alexander, a son of Alexander Alexander, continued to run the firm founded by his father, reprinting some of the books previously published as well as new material.

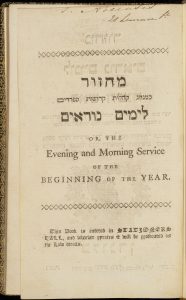

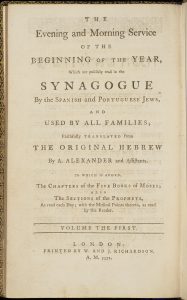

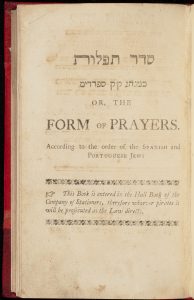

First edition

Prayer books for weekdays, Sabbath and festivals in six volumes, with an English translation, London 1771-6. The first two volumes were printed by J. and W. Richardson and the others by Alexander himself. The New Year volume contains a preface thanking those who had subscribed for copies in advance. Alexander acknowledged on the title-page of his New Year prayer book the contribution of assistants, but without naming them or detailing the extent of their help. The title-page of the book of daily and occasional prayers states that it could be purchased at Sam’s Coffee Shop near the Great Synagogue near Aldgate.

Size: 12 cms x 20 cms.

Vol. 1. 1771. New Year. The prayer book does not contain propitiatory prayers. Pagination: 129, 2.

Vol. 2. 1771. Day of Atonement. Pagination: 275.

Vol. 3. 1773. Daily and Occasional. Pagination: 2, 205, 3.

Vol. 4. 1775. Tabernacles and Simhat Torah prayers. Pagination: 2, 237, 2.

Vol. 5 1775. Passover and the Feast of Weeks. Pagination: 2, 30, 32-55, 27-194, 1.

Vol. 6. 1776. Fast days. Pagination: 2, 209, 1.

Second Edition

Some of the other festival prayer books were printed in 1788.

Vol. 1. New Year. The prayer book does not contain propitiatory prayers. Pagination: 129, 2.

Vol. 2. Day of Atonement. Pagination: 275.

Vol. 3. Tabernacles and Simhat Torah. Pagination: 2, 237, 2.

We have been unable to verify whether further volumes were printed. Cecil Roth in his Magna Bibliotheca, section B.8 no. 18, cites a second edition of the Daily and Occasional Prayers in 1788 and a third edition in 1814-15 (which would have been printed by Alexander’s son Levy). L. Alexander used this opportunity to publicise a quarrel he had with Hakham Refael Meldola. He printed on the wrapper of the book ‘A Critique of the Hebrew Thanksgiving Prayers which were said on Thursday 7th July… [1814] for happy Restoration of Peace, in which the stupidity of Rev. Raphael Meldola… will clearly be shown’. L. Alexander also had a quarrel with the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of the time and meted out similar treatment to him too.

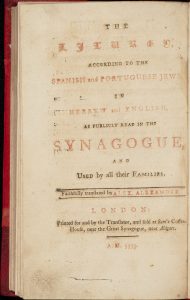

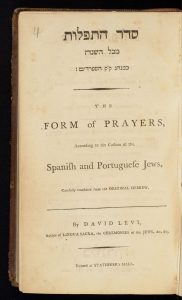

- David Levi (1742-1801)

David Levi’s translations started to be published a year after the second reprinting of Alexander’s edition. He was a scholar of repute, already having a number of learned publications to his name before he undertook his translation of the liturgy. This is in contrast to Alexander, who had no academic record as far as we know, and who had acknowledged on the title page of his New Year prayer book the contribution of his assistants, but without naming them or detailing the extent of their help. Reverend De Sola acknowledged Levi’s scholarship, and turned to his translation rather than to that of Alexander when preparing his own translation and edition of the prayer book.[7]

Levi, who was initially apprenticed to a cobbler and later became a hatter, was self-taught and throughout his life devoted as much of his spare time as he could to Jewish scholarship. In 1782 he published a Succinct Account of the Rites and Ceremonies of the Jews in which he tried to explain the faith to Jews and Christians alike, and correct some misconceptions that members of both faiths had of Judaism. He went on to publish a comprehensive Hebrew-English dictionary as well as a treatise on grammar entitled Lingua Sacra in 3 volumes, printed in London 1785-7. Towards the end of his days Levi was given a small pension by his friends as a reward for a life of altruistic service to Jewry. [8]

First edition

Prayer Books for weekdays, Sabbath and Festivals in six volumes, Hebrew with an English translation. The editor acknowledges on the title page that the Hebrew text is taken from the prayer books of the noted Amsterdam minister Reverend Samuel Rodrigues Mendes, printed in 1726.

Size: 13 cms x 21 cms.

Printed by W. Justins for the author. The books were sold by two firms of general publishers and book sellers: Joseph Johnson of St Paul’s Church-Yard and Parsons and Walker of Paternoster Row.

Vol. 1. 1789. Daily and Occasional Prayers. Pagination: 12, 1, 262, 21.

The volume commences with a dedication to Isaac Mendes Pereira, treasurer of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue. In his dedication he refers to his hope to improve on the ‘faulty, imperfect and defective translations now extant’, clearly he had Alexander’s translation in mind. He also wrote a lengthy preface in which he lays down the rules followed in his translation, and included a translation from the Spanish of Hakham Isaac Nieto’s exhortation on prayer that first appeared in his Spanish translation of the New Year and Day of Atonement prayer book London 1740, which has been previously described.

Vol. 2. 1790. New Year Prayers. Commences with the propitiatory prayers. Pagination: 141, 5.

Vol. 3. 1791. Day of Atonement. Pagination: 2, 282, 5.

Vol. 4. 1792. Tabernacles and Simhat Torah. Pagination: 199, 3.

Vol. 5. 1791. Passover and the Feast of Weeks. Pagination: 3, 206, 7.

Vol. 6. 1793. Fast days. Pagination: 213, 7.

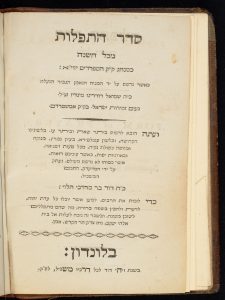

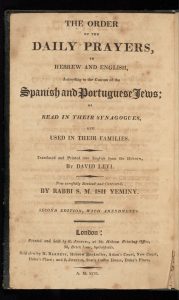

Second edition

1810, six volumes printed posthumously.

Printed and published by E. Justins, the son of W. Justins, the printer of the first edition, and sold by H. Barnett Hebrew, bookseller and I. Joseph of Sam’s Coffee House.

Hebrew with English translation. The editor acknowledges on the title page that the Hebrew text is taken from the prayer books of the noted Amsterdam Reverend Samuel Rodrigues-Mendes, printed in 1726, and subsequently revised and republished by Reverend Jacob de Silva Mendes, printed in Amsterdam in 1771.

Size: 13 cms x21 cms.

Vol. 1 Daily and Occasional Prayers.

The volume is found in several typographical variants.

- A Hebrew only edition. Pagination: 121. The variants below have the same Hebrew layout as this printing, except the last item listed.

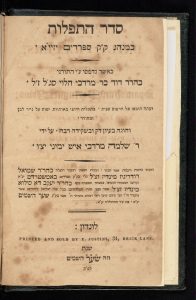

- A Hebrew-English edition. The book commences with a preface by the printer and publisher that explains that the first edition having sold out, he sought to produce a second corrected edition. As he had no knowledge of Hebrew and confessed himself to be not of the Jewish faith, he engaged one Rabbi Shlomo Mordechai Ish Yeminy to prepare a corrected edition. Rabbi Ish Yemeny we can identify as the Hebraicised version of Solomon Mordecai Ximenes, Hakham of Hamburg (1769-70). He later served on the Beth Din in London and gave expert witness on Jewish marriage laws in civil lawsuits in 1793 and 1798. He got into trouble with the community over his views in 1804, he expressed contrition, but was again in trouble with them in 1811. He was an active Freemason and published an odd work The Expected Good end … containing the birth of Jacob, his dream of the ladder, various objections on some of the verses of King Solomon. Some observations on the structure of the Tabernacle. Temple of Solomon …, etc. in London in 1800. He died in 1825.[9] The book is dedicated to the Elders of the Synagogues in England America and the West Indies. The translation from the Spanish of Hakham Isaac Nieto’s exhortation on prayer found in the first edition is absent in this edition. Pagination: 4, 336, 19.

- A Hebrew-English edition as that above except that the dedication is single-spaced and not double-spaced, and the preface is absent. Pagination: 3, 336, 19.

- A Hebrew-English edition. Dedicated to David Abarbanel Lindo, one of the lay leaders of the London Pagination: 8, 175. The colophon in this variant gives a completion date of 1813.

Vol. 2. New Year. Commences with the propitiatory prayers. Pagination: 172, 3.

Vol. 3. Day of Atonement. Pagination: 52, 55-251, 3.

Vol. 4. Tabernacles and Simhat Torah. Pagination: 172.

Vol. 5. Passover and the Feast of Weeks. Pagination: 179, 3.

Vol. 6. Fast days. Pagination: 192.

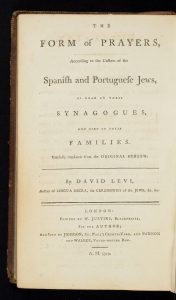

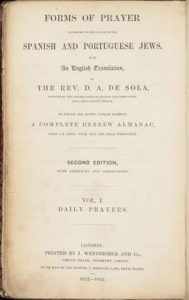

- Rev David De Sola

Rev David Aaron De Sola (1796-1860) was born and studied in Amsterdam where he received rabbinical ordination. He came to London in 1818 and was appointed minister in Bevis Marks. He preached the first-ever sermon there in English in 1831. He married the daughter of Hakham Rafael Meldola, with whom he had fifteen children. Some of the sons followed him into the ministry and several daughters married into the clergy. He wrote numerous articles and books in English, Dutch, German and Hebrew, and also translated classical Hebrew biblical and rabbinic texts into English.

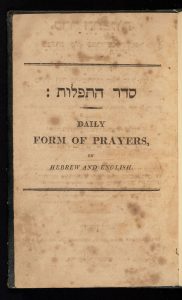

First Edition

Prayer books for weekdays, Sabbaths and festivals in five volumes, Hebrew with an English translation, London, 1836-8, printed by J. Wertheimer. De Sola acknowledged his debt to the prior scholarship of David, and not to Alexander Alexander. in working on his translation,[10] and De Sola’s work in turn provided the basis for the work of Hakham Gaster. De Sola commissioned a new font for his edition from the noted firm of type founders Alexander Wilson and Sons, who had moved to London from Glasgow in 1834. [11] The firm already had a solid reputation for the quality and beauty of its Greek type. Complaining of ‘mercenary booksellers’,[12] he chose to distribute the book himself, explaining on the title page that the books were ‘to be had of the editor, 1 Heneage Lane’.

Hymanson (p.226) suggests that the prayer books had official synagogue sponsorship; however he does not elaborate on the nature of this patronage. An official Report of the ‘Committee on the Ecclesiastical State of the Congregation’ prepared by the Elders in 1803, had suggested that the Synagogue should be involved in the process of prayer book production. In the preface to volume one (p. xiv) De Sola says that he was ‘applied to, and long refused to take upon himself so arduous a task’. He writes in the dedication (p.ii) that his translation was at the behest of Sir Moses Montefiore and that he made a number of valuable suggestions to the project. It is inconceivable that as a minister of the congregation in the direct employ of the Mahamad he did not have official approval of his undertaking, and even if he did not there would have been some record of official disapproval. However, his contemporary, Dayan Haliwa, whom we shall encounter in the next section, was an employee of the Heshaim and was a Dayan of the congregation but was not a minister of the congregation apparently acted in a more independent manner. He appears to have had some powerful supporters and perhaps this permitted him a little more licence. There is considerable evidence of Dayan Haliwa’s very strained relationship with the Mahamad over an extended period of time.

Size: 14 cms x 22 cms.

Vol. 1. 1836. Daily and Occasional prayers. Dedicated to Sir Moses Montefiore. With a preface by the editor, concluding explanatory notes, an almanac, a list of parashiot and haftarot, times of prayer in Bevis Marks Synagogue and a list of errata. The last three pages list subscribers who helped finance the publication by ordering and paying in advance for copies before printing, a common system at the time system which was known as prenumeration. Some subscribers are listed as purchasing more than one copy. Sir Moses actually purchased fifty copies. Some of these were beautifully bound and given as Bar Mitvah presents. The addresses of some of these subscribers are sometimes noted, and include many familiar locations such as Heneage Lane, Regent Street and Woburn Place. Places outside London include Clapton, Worthing, Canterbury, Sidmouth and Ramsgate. Overseas orders came from sundry and far flung and sometimes exotic locations; Jamaica, Baltimore, Lisbon, Canada and Amsterdam appear in the list. Pagination: 16, 190, 3.

A Hebrew only edition was also printed in the same year Pagination: 1,170.

Vol. 2. 1836. New Year, commencing with propitiatory prayers. At the end there are explanatory notes. Pagination: 115.

Vol. 3. 1837. Day of Atonement. Published in two parts. The first contains the services for the afternoon service prior the eve of the Day of Atonement, through to the end of the morning service, including the poem by Ibn Gabirol, Keter Malkhut (‘The Royal Crown’). He appended his own introduction to this poem, on pps. 39-40, which was reprinted in subsequent London printings of all the Day of Atonement Prayer Book. The second part commences with the additional service and ends with Negnilah, concluding with explanatory notes. Pagination: 134, 135-233, 2.

Vol. 4. 1838. Tabernacles and Simhat Torah. Concludes with a list of errata and explanatory notes. Pagination: 157.

Vol. 5. 1838. Passover and the Feast of Weeks. Concludes with one erratum and explanatory notes. Pagination: 167.

Second edition

London 1852-7 Hebrew with English translation.

Size: 14 cms x 22 cms.

Vol. 1. 1852. Daily and Occasional Prayers. The dedication to Sir Moses and Lady Judith Montefiore is shorter than in the first edition. The preface begins as that of the first edition, but subsequently diverges substantially. The volume ends with explanatory notes, an almanac, a list of parashiot and haftarot, and times of prayer in Bevis Marks Synagogue. Pagination: 14, 189, 3.

Vol. 2. 1855. New Year. Commencing with propitiatory prayers. Concludes with explanatory notes. Pagination: 115.

Vol. 3. 1856. Day of Atonement. Published in two parts. The first includes the afternoon service for the eve, through to the end of the morning service, including also from the first edition the editor’s introduction to Ibn Gabirol’s, Keter Malkhut (‘The Royal Crown’), on pps. 39-40. The second part commences with the additional service and ends with Negnilah, concluding with explanatory notes. Pagination: 134, 135-233, 2.

Vol 4. 1857. Tabernacles and Simhat Torah. Concludes with errata and explanatory notes. Pagination: 157.

Vol 5. 1857. Passover and the Feast of Weeks. Concludes with explanatory notes. Pagination: 167.

- Rabbi Abraham Haliwa (d. 1853)

Rabbi Abraham Haliwa was Dayan of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ Congregation in London and a Rabbi of the Heshaim. Very little is known about him, except that his relationship with the Mahamad was not always cordial. He edited three editions of the prayer book, and also wrote an introduction to Shulhan Arukh part 2, Königsberg 1850.

He also wrote the approbations for the following works:

הפעם אודה by Rabbi David Haliwa, brother of Rabbi Abraham Haliwa, Amsterdam 1838.

הלכתא למש”יחא by Rabbi Jacob Berdugo, Amsterdam 1844.

קול יעקב by Rabbi Jacob Berdugo, London 1844.

פתח הבית by Rabbi Abraham Belais, London 1846.

פה לאדם by Rabbi Moses Haliwa, nephew of Rabbi Abraham Haliwa, Königsberg 1853.

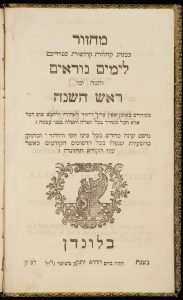

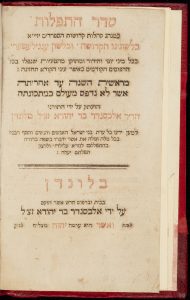

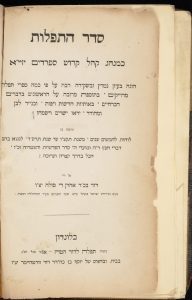

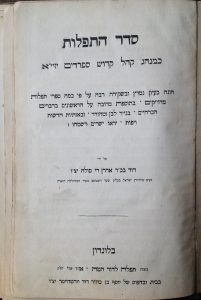

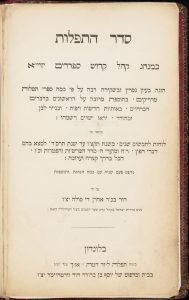

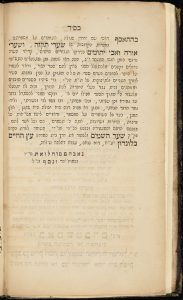

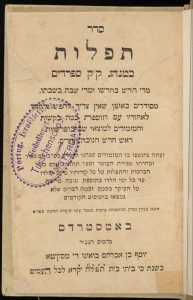

First edition

Daily and Occasional Prayer Book, Amsterdam 1843, Hebrew only, printed by Jacob Belinfante and Aaron Israel.

Size: 11 cms x 18 cms.

Pagination: 124, 43.

The prayer book is printed in two halves. The first part contains daily and Shabbat prayers and lifecycle events and occasional prayers for the minor festivals. The second part contains a selection of prayers for the three Foot Festivals.

It was prepared for publication by the Rabbi Abraham Haliwa for the committee members of the Sha’are Tiqva School and Sha’are Orah veAbey Yitomim Orphanage.

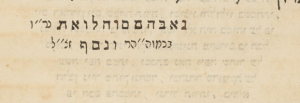

As can be seen from the picture above, Dayan Haliwa’s name is mis-spelt at the end of the introduction. The prayer book has a clearly Spanish and Portuguese flavour, such as in the text of Barukh She’amar, and the recitation of selihoth in the evening during the month of Elul. However there are also a number of features that do not accord with Spanish and Portuguese minhag practised in London at that time. For instance it contains certain bakashoth recited before the commencement of morning prayers which are still said in the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam and are also found in the Oriental rite, but do not appear either in Levi’s or De Sola’s editions of the prayer book.[14] Part 2 contains two piyutim for the hakafoth on Simhat Torah which hail from the Orient, and at the end of part 2 there is a prayer for Hannukah whose rubric identifies as being only recited in oriental communities. This edition is also noteworthy as it contains for the first time in a London associated Spanish and Portuguese prayer book the ceremony for the naming of a daughter, the zebed habat. This innovation was subsequently retained in the Abrahams and Gaster editions.

In his introduction the editor states that since there was a shortage of affordable prayer books according to the Sephardi minhag for the poor and schoolchildren, several notables of the synagogue had approached him to produce his prayer book. It is indeed true that his one volume covers all the weekday Sabbath and Foot Festival prayers, which would be the equivalent of three of the five books of the then recently published De Sola set. However, it is not clear how Rev De Sola viewed the publication of a potentially rival prayer book, or how the Mahamad greeted a publication that was not in complete accordance with the then liturgical practices at Bevis Marks.

I am indebted to Rabbi Abraham Levy for suggesting that this appears not to be an official Synagogue publication, but a private printing promoted by wealthy individuals in the community, some of whose families hailed from Morocco and Gibraltar and may have wanted a more familiar alternative to the De Sola book, the first edition of which was presumably still in print at the time.

The book is included here because of the Heshaim and other London connections of the editor, and its claim to be produced for the Congregation’s schools. However, it does not represent in its entirety the official minhag of the community at the time.

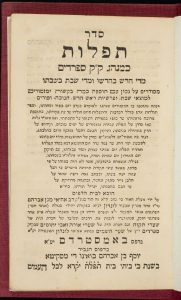

Second edition

Königsberg 1850. Daily and occasional Prayer Book, printed by Adolph Samter.

Size: 12 cms. x 18 cms.

Pagination:

Hebrew Edition: 121, 39.

Interleaved English edition as for the Hebrew edition with the addition of 233, 77.

The book was published in two formats. The first is as a Hebrew-only prayer book and the second as an interleaved English translation. Interleaving is an economical publishing technique, but produces to the modern reader an unusual result. Unlike the other editions listed here, the English text was in this case printed on both sides of one set of sheets and Hebrew text on different set of sheets of paper, i.e. each page is printed either in Hebrew on both sides or in English on both sides. The English pages and Hebrew pages were then interleaved and the sections sewn together. As a result, when the payer book is opened, the order of Hebrew and English is reversed on alternate pages.

The second issue with the prayer book, is that it contains features not present in the 1843 edition, which deviate further from the established that minhag of the London Sephardi congregation. The beginning of the book contains a picture of psalm 67 arranged in the shape of a menorah with the addition of mystical permutations of the Tetragrammaton, a feature more common in prayer books that follow a more Oriental rite. In addition, the first part of the prayer book ends with a list of common Hebrew names, each accompanied by a biblical verse with the same first and last letter as the name. Mystics considered it beneficial for individuals to recite the verse appropriate to their first name before the end of the Amidah, a practice previously without precedent in the Spanish and Portuguese tradition, but frequently found not only in some East European rites but also many Oriental rites[15]. Again, in the service for Hannukah, facing the English page 183 and Hebrew page 91b, a prayer appears which the rubric identifies as being recited only in Oriental communities. This prayer appears also at the end of part 2 of the first edition.

The translation is primarily that of Rev. De Sola. Like the first edition, the prayer book contains certain bakashoth recited to this day in Amsterdam but which do not appear either in the Alexander, Levi or De Sola translations. It is unclear who authored the translation of these passages as Dayan Haliwa’s English was not considered to be of a high standard.[16]

Königsberg at the time of printing was part of East Prussia, was later in East Germany until 1946 and is now part of Russia. It was common for foreign authors to have their works printed there.

The comments contained in the last two paragraphs of the first edition hold true for this edition, as well as the third edition also.

Third edition

Daily and Occasional Prayer Book, Amsterdam 1855-65, 2 parts. Hebrew only. Printed by Joseph ben Abraham Bueno de Mesquita.

There is some uncertainty as to the date of printing. Hebrew publishers traditionally present the date by means of a chronogram – a word or series of words in which individual letters or words are picked out to disclose the date by means of their numerical value. Such a biblical verse or phrase printed at the foot of the title-page might have some relevance to the subject or name of the book, or to the name of the author or editor. Letters would be identified by a dot over each, or by being set in a larger size or in bold type. The numerical value of such letters must be added together to reveal the date of printing. In this edition the dots over the biblical verse on title page of the first part first title page the dots are not centred, so may possibly relate to one of two letters. However, the dots on the title page of the second part are centred and give a date of 1855. Some bibliographers date the first part of this edition to 1865 and others to 1855, but both years are problematic. The year 1855 is strange as apart from this book the earliest other known publication of this printer was 1859. Also, although Dayan Haliwa died in 1853, the honorific used in the introduction in the third edition identifies the author as being alive. Joseph Bueno de Mesquita is known to have printed till 1864, so a date of 1865 is not impossible, but the issue of the honorific would be even more problematic. It is also quite possible that the two parts were not printed together, and hence carry two considerably different dates of printing. This suggestion is given credence by the fact that none of the examples examined, including those in their original bindings, were bound together; the two parts always appear to come separately.

Size: 10 cms x 16 cms.

Pagination: 144, 43.

As with the first edition, this prayer-book is printed in two halves. The first contains daily and Shabbat prayers and life-cycle events and occasional prayers for the minor festivals. The second contains a selection of prayers for the three Pilgrim Festivals.

The comments about deviations from the Spanish and Portuguese minhag in the first edition hold true here too, but innovations in the second edition such as the list of verses relating to personal names and Psalm 67 in the menorah design found in the second edition are missing. At the end of part two an additional prayer for Hanukah has been restored to its original location, having been moved in the second edition. It is only in part two that the editor is identified in an introduction that resembles that of the first edition.

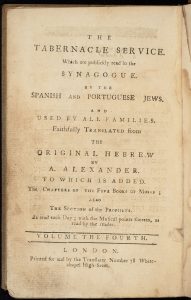

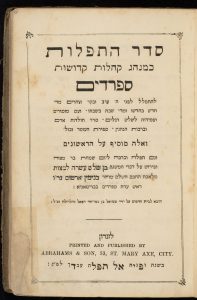

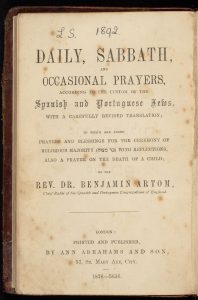

- Abrahams and Son

The printing and publishing firm of Abrahams and Son is known to have printed in London from 1870 to 1888. Their edition of the prayer book is particularly significant for the congregation because it incorporated for the first time the prayer for the Bar Mitzvah boy composed by Hakham Benjamin Artom.

Hakham Benjamin Artom

Hakham Benjamin Artom (1835-79) was born in Asti in Piedmont, Italy. He was appointed the first Chief Rabbi of Naples and in 1866 became the Hakham of the British Sephardim. In 1867 he composed the Bar Mitzvah boys’ prayer which is still recited in Spanish and Portuguese synagogues in Great Britain and the United States till this day.[17]

He published numerous sermons and synagogue odes, and at least one sermon in Italian was printed before he came to England. Some of the sermons that he delivered in London were printed separately, and subsequently a major collection was published in London in 1873 and a second edition in 1876 with a slightly different selection of sermons.

Select bibliography:

ויהי בחדש השמיני Poem in honour of the installation of Rabbi Mordehai Ashkenazi as Rabbi of Asti, Biella 1858.

מזמור לתודה Poem in Hebrew and English in honour of supporters of the Spanish and Portuguese educational establishments in London 1878.

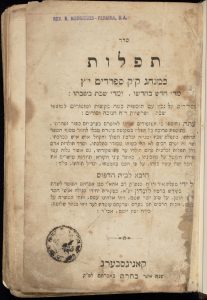

First Edition

Daily and Occasional Prayer Book, London 1875. Hebrew only. Prepared for publication by Samuel Meldola (the son of Hakham Rafael Meldola). There is no evidence of any formal synagogue involvement in this publication and the title page does not say that it was printed with the approval of the Mahamad.

Size: 12 cms x 18 cms.

Pagination: 234, 74, 40, [7].

The work was printed in four parts. The first contains daily and occasional prayers, the second part prayers for the pilgrim festivals, the third part Torah reading for weekday and Shabbat afternoon, and the fourth part Hakham Artom’s prayer and misheberakh for a Bar Mitzvah and Reflections on the Bar Mitzvah ceremony. Between 1867 when the prayer was first printed and 1875 when this prayer book was printed the prayer was distributed on printed sheets. A reprint with minor corrections and with the addition of Artom’s Reflections appeared in 1872. In the first part of the prayer book there also appears the ceremony for the naming of a daughter, the zebed habat. This innovation had previously appeared in the Haliwa editions described in the previous section. This ceremony was also subsequently retained in the Gaster edition.

Second edition

Prayer books for weekdays, Sabbath and Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur in three volumes, with an English translation. London 1876-9. Printed and published by Ann Abrahams and Son.

Size: 12 cms x 18 cms.

The translation was based on those of De Sola and of Isaac Leeser printed in Philadelphia 1837-8 (six volumes), with additions and emendations by an unnamed editor.

Vol. 1. 1876. Daily and Occasional prayers. The layout of the Hebrew pages is identical to the 1875 edition. However, the second part of the first edition (which deals with the Foot Festivals) is absent. Pagination: 234, 40, 7.

Vol. 2. 1879. New Year prayers. Commencing with propitiatory prayers. Pagination: 6, 155, 1.

Vol. 3. 1879. Day of Atonement, in two parts.

Part 1. Pagination: 1, 189, 1.

Includes the services for the afternoon service for the eve of Kippur , through to the end of the morning services, with De Sola’s introduction to Ibn Gabirol’s poem Keter Malkhut (‘The Royal Crown’) and his concluding notes.

Part 2. Pagination: 2,145, 1.

Commences with Musaf and contains all the remaining prayers for Kippur.

We have been unable to trace any copies or bibliographic references to prayer books for any of the other festivals.

- Hakham Moses Gaster (1856-1939)

Hakham Moses Gaster claims the distinction of being the first and only Ashkenazi Hakham of the congregation 1887-1918. He also served as principal of Judith Lady Montefiore College 1891-96. Hakham Gaster was a language lecturer of Romanian origin and came to Britain in 1885, after being expelled from the land of his birth for political reasons. He became a lecturer in Slavonic languages at Oxford and was noted as a researcher in many different fields including Semitics, folklore, Slavonic studies and Samaritanism. His literary legacy is impressive not only in terms of quality and quantity but also scope[18].

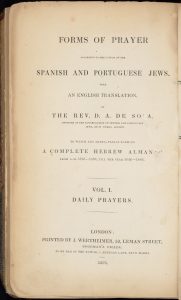

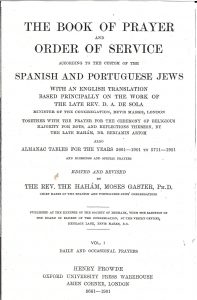

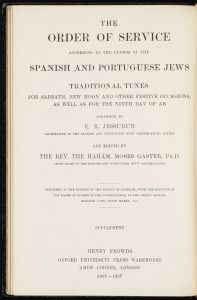

First Edition

Prayer Books for weekdays, Sabbath and Festivals in five volumes, Hebrew with an English translation ed. by Rabbi Dr. Moses Gaster, 1901-1907 printed by Henry Frowde at the Oxford University Press Warehouse London, which was an imprint for Horace Hart at the Oxford University Press. The prayer books were published by the Heshaim and hence mark the Heshaim’s first formal involvement in the in the production printing and distribution of the prayer book, a practice that has continued since then.

At the end of each volume is an appropriate selection of melodies. The edition appears to be the first and only set of ‘traditional’ prayer books for the entire year ever printed with musical notes in the western style of musical notation. Musical notation had previously appeared, sparingly, in other Jewish liturgical works, the earliest being a Haggadah printed in Königsburg in 1644, but was a comparatively rare practice.[19] These were arranged by the then choirmaster E. R Jessurun, and edited by Rabbi Gaster.

The Gaster edition may have been timed to coincide with the bicentenary of the opening of Bevis Marks. The editor acknowledges the debt he owed to the work of De Sola in preparing his new translation.

Size: 14 cms x 22 cms.

Vol. 1. 1901. Daily and Occasional Prayers. Pagination: xxx, 246, 3, 69. The book commences with an introduction by Hakham Gaster and is followed a reprint of the preface to the first De Sola edition and a further preface by Dr Gaster. Pps. 224-229 contain the notes on the translation from the first edition of Rev. De Sola. Pages 230-231 contain a reprint of the Reflections on the Bar Mitzvah ceremony by Hakham Artom. Pps. 232-236 contains a list times of prayer at the London synagogues and a 50 year calendar. Also included is a list of Haphtaroth for each Parashah, as the Spanish and Portuguese tradition varies occasionally from the Ashkenazi and oriental rites.

At the end of the book is a supplement printed in 1907 containing traditional tunes recorded in standard musical notation. As was noted above, the melodies were recorded by the choirmaster E.R Jessurun, and edited by Dr Gaster, who also contributed a preface. The example we examined has a note on the reverse of the title page saying reprinted 1921. It is possible that there was an over-run or excess of prayer books printed and the musical supplement was reprinted on a hand-to-mouth basis. The converse is also possible and that the supplement was sold separately and had to be reprinted as demand from the choir amongst others outstripped the initial supply.

This volume, being for daily and Shabbat use was the most reprinted of the volumes. It was also revised more than any of the other volumes. It is almost impossible to list all the changes that took place in each new reprinting. Apart from the changes made to the prayer for the Royal Family, a selection of the most major changes are listed below.

- Reprinted in 1947 as per the first edition.

- Reprinted in this publication was authorised by Hakham Solomon Gaon, with a reset translation, and a new introduction by Hakham Gaon in addition to those of De Sola and Gaster. This edition added a prayer for ‘The Land of Israel’ and Maoz Tsur at the end.

- Reprinted in 1973 as per the 1958 edition.

- Reprinted in 1991 as per the 1973 edition. This was a well-produced corrected edition, based on the original Gaster Hebrew typesetting to which the changes introduced in 1958 were remade. A short run was also produced in a white binding, without the music section, for the marriage of Becky Lagnado and Stephen Hendeles on 5 May 1991.

- Reprinted in 2002 as per the 1991 edition. This was an inexpensively reproduced in perfect (i.e. glue-backed) binding, without music, and with additional page 108a containing the priestly blessing in Sabbath morning prayers only (not in musaf). The prayer for ‘the State of Israel’ appears in the correct place, with an added reference to ‘soldiers’.

- Reprinted in 2003 as per the 2002 edition.

- Reprinted in 2010 This was a well-produced edition with substantial corrections, based on the 1958 edition (since the artwork produced in 1991 had been inadvertently destroyed) and with a new calendar section compiled by Dr Julian Gilbey.

Vol 2. 1903. New Year prayers, but commencing with propitiatory prayers. On page 143 is a list of dates on which the New Year would fall till 1951. This is followed on pages 144-152 with the traditional tunes in musical notation. Pagination xi, 152.

Reprinted in 1936 and 1971. A revised version was printed in 2008.

Vol 3. 1904. Day of Atonement. Pages 455-46 contain a reprint of Reverend De Sola’s introduction to the poem of Ibn Gabirol entitled Keter Malkhut (The Royal Crown). Pages 265-266 contain various notes of De Sola on the text. On page 266 is a list of dates on which the Day of Atonement would fall till 1953. This is followed on pages 267-280 with the traditional tunes in musical notation. Pagination: xvi, 280, 1.

Reprinted with amendments in 1934, 1969 (a major re-working) and 1987.

Vol 4. 1906. Tabernacles and Simhat Torah . Page 186 contains notes from the De Sola edition and additional notes of Hakham Gaster. Pages 187-188 contain rules pertaining to the succah, lulab and the Simhat Torah service. On page 189 is a list of dates on which Tabernacles would fall till 1955. This is followed on pages 190-209 with the traditional tunes in musical notation. Pagination: xx, 209, 1.

Reprinted with amendments in 1931, 1960, 1980 and 1992. The 1992 printing involved a major reworking of the text.

Vol 5. 1906. Passover and the Feast of Weeks. On page 203 is a list of dates on which Passover and the Feast of Weeks would fall till 1955. This is followed on pages 204-233 with the traditional tunes in musical notation. Pagination: xx, 233, 1.

Reprinted with amendments in 1931, 1960 and 1974.

Fast days prayer books

Since the prayer book for minor fast days was last printed in 1810 there was a pressing need to produce a new fast book. For the sake of expediency in 1965 an offset print was made of the American Leeser[20] edition printed in Philadelphia 1867.[21] The book was printed in London, jointly with Congregation Shearith Israel and Hebra Hased Va-Amet of New York, in its original smaller format of 13×19 cms., pagination 9, 216. The minor fasts book was reprinted in 2000 in the larger standard size of the Gaster books of 14 cms. x 22 cms. On this occasion an offset print was made of the American Leeser 1st edition printed in Philadelphia 1838, with significant corrections listed in the addenda. Pagination: 7,186.

- The 2011 Heshaim edition.

Prayer book for Sabbath mornings in one volume, Hebrew with an English translation, London,2011. Printed by Smith Settle, Yeadon and published the Society of Heshaim. Pagination, 251.

Size: 12 cms x 19 cms.

Approximately one hundred years after the Gaster edition, a new edition of the prayer book was produced in 2011. There were several factors motivating this new edition.

- The translation prepared by Gaster was felt to be a barrier to prayer and to need updating.

- The Oxford University Press which had printed the Gaster prayer book until about 1990 closed its commercial wing, and the font cut for the De Sola edition had long before been too worn out to use. It was felt that the process of updating and emending the prayer book should be handled ‘in house’, as had orders of service for special occasions for some years.

This new edition was seen as a trial for a new edition of the daily prayer book and a new complete Shabbath prayer book that is currently being completed. The 2011 prayer book contains several new features. The prayers are arranged as far as possible in the order in which they are recited, obviating the need to turn elsewhere for a particular prayer. It contains for the first time the Hebrew and Portuguese formulary used in the liturgy for calling up and special prayers recited on various occasions, some of which had never before been printed. It contains all the prayers that could be recited on a Saturday morning, including prayers for the intermediate Sabbath of Succot and Pesah. The work was initiated and coordinated by the Thesoureiro, Dr Jeremy Schonfield, who proposed the order of texts and oversaw the work of other members of the team. The Hebrew for this edition was arranged by Dr Jeremy Schonfield and included rubrics prepared by the late Professor Raphael Loewe and reviewed by the late Rabbi Abraham Gubbay. The translation was completely revised by Lucien Gubbay, in consultation with others, in a more contemporary style. The contemporary Hebrew type face is a specially emended version of Frank-Rühl. The volume was issued with the rabbinical approval of Rabbi Dr Abraham Levy OBE the then Spiritual Head of the Congregation, who added a new introduction to the prayer book. The Thesoureiro contributed a preface.

Heshaim is now working on a new edition of the daily prayer book and the Sabbath prayer books which, because of considerations of thickness and utility, will be split into two volumes, a weekday one and a Sabbath one.

[1] See Samuel E., At The End Of The Earth – Essays on the History of the Jews of England and Portugal, The Jewish Historical Society 2004, p.188.

[2] The episode is recounted by Hymanson, pp. 184-5.

[3] Roth, pps. 302-3.

[4] These small pamphlets are described in Roth, pp. 302-3.

[5] The first sermon printed in English is dated 1803 and was a ‘Penitential Sermon preached in the Spanish and Portuguese Jews Synagogue … 19th October 1803… [for the] success to His Majesty’s arms’ by Isaac Luria . The last sermon to be printed in Spanish was the funeral oration delivered in 1820 by Hakham Raphael Meldola for King George III.

[6] A comparison of some of these differences can be found in the work Keter Shem Tob by Rabbi Shem Tob Gaguine (1884-1953), who was the Principal of Judith Lady Montefiore College and also the Ab Bet Din of the Congregation.

[7] De Sola, Daily and Occasional Prayers, 1st edition vol. 1, 1836, preface p. xiv. On page xiii he describes the work of Alexander as having ‘long ago sunk into merited oblivion’.

[8] For further information on David Levi and his scholarship see ‘Jewish Enlightenment in an English Key’ by David B. Ruderman, Princeton University Press, 2000.

[9] James Picciotto in ‘Sketches of Anglo-Jewish history’ identifies Ish Yemeni in the 1795 case of Lindo v Belisario as Is. Jimenez (p. 102) former last Hakham of Hamburg which Israel Finestein corrects to ‘Isaac Ximenes’ (n. 6, p. 458) probably following Hyamson (p. 193) but the original court report has “Solomon Mordecai Ish Yemene” as the name of the expert witness. There was also book editor and corrector of that name who edited two volumes of the work Markebet Hamishnah by Rabbi Solomon of Helma printed in Frankfort 1750-82, The same name also appears as copyist in a nineteenth-century Middle Eastern Kabbalistic scroll in the Lehman collection in New York catalogue no. K86. However, we have been unable to connect any of these people to the editor and corrector of the second edition of Levi’s prayer book.

[10] De Sola, Daily and Occasional Prayers, 1st edition Vol. 1, 1836, preface p. xiv. On page xiii he describes Alexander’s edition as having ‘long ago sunk into merited oblivion’.

[11] P. xvi.

[12] P. xiii

[13] The title page of Yoreh De’ah has two variants.

[14] Although not printed in the London prayer book, the tunes of these poems are recorded by Emmanuel Aguilar in ‘The ancient melodies of the liturgy of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews’, London 1857 with a translation by Reverend David De Sola. De Sola would have been familiar with these tunes from his early years in Amsterdam and it may be that he recorded them for posterity as a historical record, rather than as a reflection of the liturgical practices of London at that time.

[15] This custom was subsequently adopted by the Amsterdam community. The earliest Amsterdam prayer book I could trace it to is סדור ניב שפתים printed in 1872. It was produced by R. Montezinos and J. Lopes Cardozo. The practice may have been adopted earlier; however I was unable to check all the relevant editions.

[16] See Hymanson, p. 311. The translation differs from the translation of De Sola referred to in the first footnote.

[17] Bar Mitzvah boys’ prayer was first printed in America in the 1878 Philadelphia edition of the daily prayer book edited by Reverend Abraham De Sola, minister of the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation of Montreal.

[18] A full bibliography of Hakham Gaster’s writings is included in the Gaster Anniversary Volume, ed. Schindler, B, and Marmonstein M, Taylors Foreign Press London 1936, pps. 21-37. This bibliography was subsequently updated by Schindler for the Gaster Centenary Publication published by the Royal Asiatic Society, London 1958 pps. 23-40. The list records 281 books and papers excluding general contributions to learned journals and reviews.

[19] Other prior examples include some music in a prayer book of the Reform Congregation of Berlin printed in 1891 and a handbook for cantors printed in Prague in 1877.

[20] Isaac Leeser (1806-1868) was born in Germany and emigrated with his family to America in 1824. He served as Hazzan in the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in Philadelphia 1829-1850. He published widely, and was particularly noted for his translation of the Torah into English in 1845.

[21] The Leeser translation of the prayer books bear the title סדור שפתי צדיקים.