Kedoshim and Canonicals 5776

in Rabbi Morris Blog

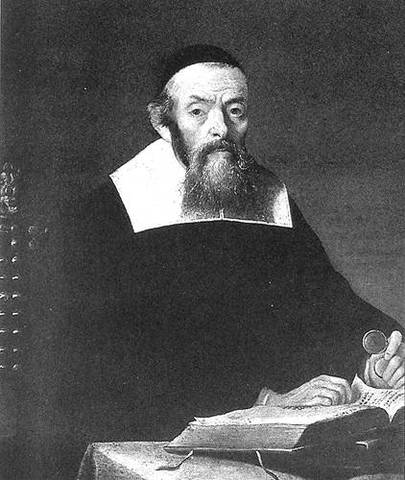

R Yaakob Sasportas, Rabbi in Amsterdam and London, 17th Century

One of the most noticeable features at many of the Spanish and Portuguese synagogues are the canonical robes worn by the rabbis and hazanim (often called ministers). They are striking because they are so similar in style to gowns traditionally worn by many Protestant ministers. Wearing them therefore seems to transgress the Biblical prohibition of ‘thou shall not follow in their ways (Leviticus 18:3).’ Rambam codifies this law to include the imitation of Gentile dress (Abodat Kohabim 11:1). How then are Jewish religious officiants permitted to wear such garments? Indeed not only were they worn by the Western Sephardim, but also by Jews in North Africa, and even by Ashkenazi rabbis in Western Europe such as Samson Raphael Hirsch. I too wear them on Shabbatot.

The Talmud identifies an exception to the prohibition, which at first glance seems to answer our problem. The Talmud states that if one needs to dress ‘as the Gentiles’ for professional reasons such as in order to be recognized as an expert, then wearing ‘Gentile dress’ is permitted. While this would seem to apply to our question, it does not. According to the Maharik (Yosef Colon Trabotto, 15th Century Italy: Response #88), the Biblical prohibition of ‘not following in their ways’ is not a sweeping clause, but rather only applies to a particular scenario. Namely, to the Gentile ‘traditions’ that seem to lack any rationale or function. One might include a Christmas tree or ‘trick or treating’ in such a category. Maharik argued that when the rationale for such ‘traditions’ are not clear one must be concerned that the true origin lies in some idolatrous/foreign practice. Accordingly, anything which is not a ‘tradition,’ but is rather just a style of dress, or a form of entertainment, would not be included amongst those things which are prohibited in the first place. By that same token, any practice which is known to originate in foreign worship is prohibited anyways (even without the prohibition ‘to not follow in their ways’). Accordingly, the Talmudic dispensation for professional attire would seemingly not apply to our canonicals as their origin in foreign worship is not in question.

Dr David de Sola Pool

Dr David de Sola Pool (1885 – 1970) of New York’s Shearith Israel seemed to understand this nuanced position well. He argued to the Mahamad of Shearith Israel that he should not be required to wear distinctive clerical dress when not leading religious services. He insisted that to wear such dress when involved in mundane activities (as was the practice of Christian clergy), was in fact a breach of Biblical law, while to wear them while conducting divine services, was not. He wrote “the wearing of clerical garb on non-religious occasions, with its segregation of the Rabbi in a priestlike caste apart from the general community, is distinctly and definitely a Christian custom, contrary to the letter of Jewish law and spirit of Jewish life…my Jewish loyalty [w]ould be weakened by conforming to traditions contrary to my orthodox Jewish scruples and conscientious convictions.”

Rabbis of the London S&P Sephardi Community